The Most Essential Things Lie in That which is Concealed

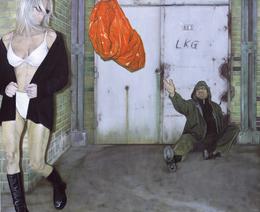

A discussion about abstraction in figurative paintings, art and non-art and the distance between him and serial-paintings. Formally strict, he revolts against the merciless deconstruction of the modern age. Since he doesn't endeavor to unravel or to demystify, we are henceforth even more induced to enter the realm of what is possible to experience.

Siegt: According to a common prejudice which is widespread among admirers as well as detractors, here in Germany we understand painting from the point of view of ”realism” as if a painting could be directly based on a given observation. May I ask you to tell us straightforwardly about the way you understand painting.

Kalaizis: The European painting tradition in itself shows us, and this is apart from the different, flat conception of realism from the 19th century, that painting is an invented reality. Before and after this time this had always been obvious. Whether or not one works figuratively, abstraction or the ability to create abstraction should be an essential skill.

S: I’m asking since the question of reduction or of avoiding and omitting is of central importance. Could you say that the process of abstraction serves simplification?

K: Well, you could say so, although I need the purity and clarity of the background in order to provide a support for the scenarios which are not necessarily so obvious. What I need is the perspective order of space, the interaction of color, which includes the utilization of a strictly limited palette.

S: According to this could one say that the perceiving observation ought to be complemented by a constructive imagination.

K: Yes, no question about it! Yet in your question you have expressed a general misunderstanding, as if there were an almost unbridgeable contrast between representation and abstraction. Of course an abstract image can exist without any form of representation, but a functioning representative image can never exist without abstraction.

S: These days a lot of people understand abstraction to be something removed from reality. Just as if the term in itself does not have a relationship to life, as if abstraction is based in a sphere of missing connectivity. I understand that you are of a different opinion and perhaps you could discuss this a bit?

K: Just recently I was at a terrible exhibition, where I noticed an typical example of this. In this picture, which was a painting, you could see a garden in the summertime. There were a considerable number of trees with countless apples and oranges hanging from them. In front of these, about in the center of the picture, there was a table with some chairs. Leaning on this table there was a shovel, and on one of the chairs there were even some garden scissors. In this image there was also a man, who seemed to be determined to attack the observer, which in this case meant me. Not only did this guy wear a feather in his hat, he also carried a briefcase, and from that briefcase the title of a book, painted very precisely, was peeking out. Although this painting was undeniably executed with a sound craftsmanship, it was still a bad picture.

S: So you’ve used an example to the contrary as an explanation?

K: This is because in that picture, and there are many of these ultimately dumb pictures, things are only being described one after the other without there being a need for this. The need to present some things and to omit others is a matter of the consciousness, or technically speaking, a matter of the human processor. I judge the quality of an image based on the spaces between objects which seem significant at first glance. The space in-between is of the same importance and thus demands the same amount of concentration. The equal representation of things in the sense of a homogeneous description, no matter how well executed, is tiring and shows that the painter is limited within his own métier, since he is not able to think on a broader scale.

S: This might be connected with the fact that some artists see the degree of resemblance which their representations achieve as a criterion.

K: I agree with you. And copying is a mere matter of craftsmanship, which in my opinion does not yet have anything to do with art. I’m also against a kind of painting which ties its value only to the degree of recognisability. I’m against painting the already existing, against portraits, against unfiltered landscape painting, so to speak against the entire palette of the ”summertime garden.” Wouldn’t it be a skillful application, if you manipulate the object and thus create a different situation, which bears a somewhat irritating factor. Thus, I am able to oppose something and at the same time I’m able to enjoy certain aspects of it. This is my constant opposition, a contradictory search for a scale which unites both the high and the low notes. Just as after my childhood I always felt the urge to interrupt everybody who started to speak with great significance and to say something ridiculous; I’ve used this attitude later for myself and have applied it in my painting.