A second story by Christoph Keller after a Kalaizis-painting

In Switzerland born and in New York living author Christoph Keller "The Interference of Angels" sketches with the second story to an other Leipzig-Kalaizis painting an absurd parallel world

A miracle has even deeper roots,

Something like error,

some profound defeat.

‑Muriel Rukeyser, Fable

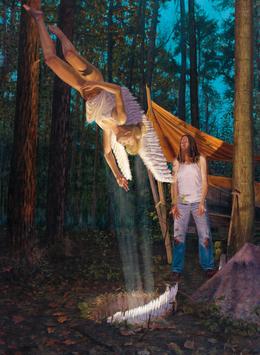

He needed the money Pentagrass offered him for modeling, if that was what you wanted to call it: putting on dirty jeans, an unwashed undershirt, a silly wig and a surprised look. People stayed away from the restaurant in Grimma, where he worked as a waiter, and more and more often, when Johan arrived for work, he found the door shut and a Closed sign on it. He had taken the afternoon off, without asking the restaurant owner. Eventually, Robert would let him go anyway, with the economy what it was. Johan stopped. He leant the shovel against the closest tree, next to the pile of soil, heavy with last night’s rain. He felt exhausted. He looked up. Above him nothing but an auspicious canopy of leaves. Good, Pentagrass thought. Johan had come early. >He had brought the rusty green Wartburg he wanted in his painting, and he had parked it exactly where he had told him. He had built the makeshift tent out of the sticks and the dustsheets Pentagrass had provided him with, and he had even started to shovel. Now that Pentagrass had arrived with the rest of the equipment and with Marie, the model for the angel, Johan had put the shovel aside and assumed his pose. “Just look surprised, Johan” Pentagrass said, stepped out of the clearing, where he was part of the wood, and looked at the scene through the lens of his camera. It was understood that they wouldn’t acknowledge each other during the process of setting the scene for the painting. It was the essence of the painting. It was the only way painter and model could get lost in the painting. W353. Mysterious as ciphers, as clouds, crucial as the right light, a part of the license plate of the pickup was visible between Johan’s legs. Behind Johan, there was now a stable, the pregnant sky.

The trees looked fresh as though they had just been planted. All sorts of peaceful sounds could be heard, the rustling of leaves, the rapping of a woodpecker, the fluttering of wings. Pentagrass’s previous work, The Ritual, had also originated in the clearing. Here, months ago, collecting mushrooms, he had found the giant root that, half-freed from the earth, had become the centerpiece of the painting. He had dragged the root to his living room, to the annoyance of his wife. For weeks bugs and ants had crawled around their apartment, trying to find their way back to the woods. The Ritual showed Pentagrass in an undershirt (the one Johan was wearing now) and suspenders from the back, holding the roots in midair with the help of a rope while a woman is watching disapprovingly. (The woman in his real life came to appreciate the painting.) He looked at Johan intensely. Like an actor who knew his role but not the movie he was in, Johan knew what to wear and where to stand, but he didn’t know anything else. He didn’t know what to expect, if anything. He certainly didn’t know that Pentagrass felt forced to come back to the scene of crime of his previous painting. Johan didn’t know that Pentagrass felt mysteriously compelled to paint another angel painting after Make / Believe and Making Sky. It didn’t occur to him that he could become part of the painting, with maybe no way out. He had been told to look surprised but he didn’t know that his surprise would be genuine. Quickly, Pentagrass stepped into the scene, put a crown of feathers into the still-open hole, and withdrew.

Johan felt sick, falling apart. He felt it physically, cheeks narrowing and paling, blood thickening, heartbeat slowing. Was he out of work by now? He couldn’t check the time, not while posing. It must be past four, the restaurant had opened, and his, and the pick-up’s, absence noticed. He glanced at Pentagrass, who nodded: that was a violation of the rules! Ligh t— a geyser of light — shot out of the hole, and it filled with feathers, white as those of a goose, a swan. Johan did what people often do when they don’t understand — he went on a search for his cigarettes. He didn’t care about abandoning his pose, even leaving the scene. He found them on the passenger’s seat. The car smelled of age and abuse. Back at the hole, it felt inappropriate to light up.

Clio, pregnant, banned smoking in her presence. Sometimes Johan did it anyway. She was in her tenth week. There was still time for decisions. They didn’t have the money for themselves, much less for a child. He had promised her — the last time only a few hours ago when Clio had thought he had left for work — to pull himself together, to work even harder, smile more for tips and maybe even a raise, despite it all. He flipped the cigarette into the hole. It was swallowed by the feathers, teeth of the earth. Anger hitting the wrong target. He longed to be in the restaurant, smiling, with the Wartburg unstolen, Clio unpregnant, the cigarette smoked, waiting on impatient costumers, hungry for Robert’s overpriced organic gourmet meals. Instead he was here, wearing somebody else’s dirty undershirt, this ridiculous long-haired Jesus wig. Click!, and Johan’s surprised face was captured. Pentagrass put the camera on the ground, stepped into the clearing and slowly lowered Marie. Marie, who assisted Pentagrass’ wife in her tailor shop, was wearing a climbing harness underneath her set of swan feathers and her light white undershirt. She was attached to a set of ropes, and the ropes were attached to two trees. When her head was on a par with Johan’s, Pentagrass secured the ropes and stepped out of the clearing. Marie was looking into the light coming out of the hole, Johan, entranced, was gazing at the angel’s golden hair. “Now bend your right knee, Marie,” Pentagrass said. “The other one and not so much, good, stop right there. And extend the left arm, point two fingers at the hole. Do not look at Johan.”

Pentagrass had never worked with Marie before, but now that she was solidly hanging from the sky he had a premonition of perfection. Instinctively, Johan opened his hands toward the angel. “Shall I …,” knowing how helpless he sounded as he said it, “… catch your fall?” “That’s not necessary,” the angel said with the most angelic smile. “But thanks anyway, Johan.” She stopped in midair. Her wings didn’t move. Her hair was a mystery in the light coming from the hole. Her shoulders were naked, and so were her arms and legs. As she was descending head first, her shirt had slipped, exposing her crotch which she covered with her right hand. Johan’s worries grew. He didn’t want the angel’s longing nakedness to come between him and Clio. He felt the desperate urge to hug Clio, to put his ear to her stomach and listen. Helplessly, he announced, “I do want the child. I really do and … I hope it’s not too late. I hope she hasn’t gone to the doctor yet. I hope she still loves me. And somehow, Clio,” he said as though she was standing in front of him, “somehow we’re going to make it. We are, Clio, I know it.” It had gotten so dark suddenly. For a moment, there had been no sky beyond the trees. Johan knew that the angel wasn’t Clio. But he was convinced that Clio could hear him through the angel. The angel didn’t say anything. It wasn’t necessary. Then the colors came back, fiercely, they were the colors of the dying sky, dusk sipping its misty blue, its once so reassured cerulean. Johan stared. Empires collapsed but children were born. Finally he said, “No more excuses. I’ll talk to Robert. Maybe it’s not too late. I’ll work for tips and a raise. Times will get better, they always do. I’ll stop smoking, Clio, I’ll do anything you want me to.” Then the angel was gone, and the forest settled for a dose of heavenly silence.

Like all great paintings, Pentagrass’s new one became the illusion about an illusion: reality and its flipside. A painting that is more than a painting is a vision. It is an allegory of painting. That has maybe never better exemplified than in Johan Vermeer’s painting of that name, in it a model posing as Clio, the muse of history (why of history in an allegory of painting wasn’t of Pentagrass’ concern so many centuries later), in it Vermeer as The Painter from behind. It is a painting that puts each of its objects in its precise context. Nothing is left to chance. Nothing else becomes possible. This is also true for the painting The Ritual: Just look where the red curtain is and how it folds. How the root hovers. How the woman disapproves. Look at the ropes. How they hang. Look at The Painter, how he holds the rope that holds the painting together. Look at the mysterious sign, how green it glows, how we’re not supposed to really understand it like a geyser of light erupting from the wounded earth.

Intensely, Pentagrass stared at the new work. He had worked on The Interference of Angels for six weeks, and now it was finished, leaning against a wall in his naked studio. Now the only consolation was the slow drying of paint. He stood back and thought of Johan who, in the meantime, had lost his girlfriend and his job. It was overwhelming, the perfection of art and the imperfections of life. He looked at the angel’s hand, covering her crotch, but could only think of the layer of green primer and the canvas underneath. “Miracles have even deeper roots,” the angel said. Johan’s child — a girl — grew inside Clio. She would do well in this difficult life. Quickly, Pentagrass turned the painting upside down, and suddenly everything made sense.

©2010 Christoph Keller/Aris Kalaizis

Christoph Keller, born in 1963 in St. Gallen, is the author of several novels, essays and plays, most recently the novella “A Few Familiar Things” (2003), the autobiographical novel “The Best Dancer,” (2003), the play “The Foundation,” (2004) and the photography show “Eye Catcher” (New York, 2006). In the spring of 2008, The State of Last Things was published, the third novel with Heinrich Kuhn as Keller+Kuhn. He divides his time with his wife, the poet Jan Heller Levi, between St. Gallen and New York City. “The Interference of Angels” (The Ritual) is his second story after a painting by Aris Kalaizis.